In the midst of the conversations about the “crisis of the humanities” that seemed pervasive throughout my graduate career, I developed the conviction that my value as an educator was not the product of my ability to deliver content.

One more time, for the people in the back:

My purpose as an educator is not to deliver content.

“Content” is all of the stuff that is supposed to “be on the final exam.” These are the facts, the names, the three important things that every student should know about a historical figure to write in response to an “Identification Question.”

When I was a student on the cusp of the Age of Google, Content used to be what made you interesting at a cocktail party. But in the current day, Content is what you find on Wikipedia.

Obviously, one cannot teach without content. It’s the context of all of our historical work. But the more easy it became to access content, the more I wondered what I was doing at the front of the room. Was I, an individual in whom my parents, the state of California, numerous grant-funding organizations, and my current and past research institutions had invested so many resources, truly just a Meat Wikipedia with interactive features?

I doubted.

As a grad student TA, I had often sat in lecture halls thinking about the nuance that was lost in the survey lecture. Some topic that we debated for hours in a seminar would flatten out and become a farce in the context where we conveyed our knowledge to undergraduates. Something was simply some way. It was somehow our jobs to describe how “something really was,” and then to explain why it was important to understand how that thing came to be, and then test students to make sure that they heard us correctly (and agreed with us). The classroom was a strange kind of intellectual battleground. A place where instructors forced their conclusions on students. A place where lecturers slaughtered entire sub-fields of nuance. A place where scholarly vendettas were trotted out and executed while an unknowing, uncaring audience stared blankly at the podium. A place where where students were compelled to agree with whole worlds of assumption and argument that had been cast as fact by the instructor.

I began to detest how we tore down history in some classrooms, only to build it back up in others. How some of us were invited to participate in the first process, and our work in that larger project was concealed from all others.

I began to hate Power Point.

Those slides mocked me. Decades of debate distilled into the five items (with one to four sub-items) that the student must retain about Subject Heading.

Why go to a lecture? Why listen to an instructor? Why talk about anything, ever? How could I blame the students who sat, laptops open, recording the Power Point word for word (or simply downloading it) and scrolling through social media sites, or doing homework for other classes while the instructor droned on? Why were we here together? Why did we bother? What was I supposed to be offering these young minds, that had dragged themselves out of bed to sit in this room? What did I offer beyond “content”?

The answers to those questions span subjects beyond the scope of this single post, but one thing became clear: the point was not for me to distill complicated thoughts and not-quite-known things into easy-to-digest bullet points. The point was not for me to collapse what was beautiful because it did not lend itself to easy consumption. The point had to be the opposite: to take what seemed easily distilled and communicate what had been lost, or how it had been lost, or how something new had been created when we claimed to be summarizing, or how to interact with it in different ways. To get over viewing intellectual exchange and fruits of research as “content.”

The point was not the content, but the power dynamics, the knowledge practices, and the closing off and opening up of possibilities in the production of content.

I didn’t want students to think of me as the object that decided “what is going to be on the exam.” I didn’t want students to feel forced to parrot my world view. I didn’t want young people come to the class looking for facts (or dreading listening to my interpretation of the world as fact). I didn’t want them to look to me for content.

So I decided to re-think how we interact in the classroom. And one of the first things I decided on was to invite students to question the neutrality of the category of “content.” I began thinking through this problem as I sat down to formulate my first freshman seminar. I started by choosing an approach to the survey course that would suit my goals. My freshman introduction to “History of the Chinese Empire,” I inform students on the first day, is not a collection of facts and stories from Chinese history, but rather the history of the construction of the notion of a “Chinese Empire.” We approach the question historiographically. We learn about how different people at different times thought about, wrote, and grappled with the problem of history. We learn about different technologies for recording history, different interpretive lenses dependent upon historical framing, different assumptions about history based on textual practices. By the end of the quarter, the goal is for students to be able to read twentieth-century Chinese history as the product of a couple of millennia of historiographical innovations; as the product of the invention, rejection, and adaptation of a tradition of Chinese empire.

This class was all about how the “content” of Chinese history was less important than the mechanisms producing and consuming it. But, as a survey that spans over two thousand years, it contained a higher-than-usual amount of content. Most of my classes are seminar style, and depend on discussion, but this particular class was unavoidably fact-full. The content in that class was merely the context for a larger argument about historiography, so while it was necessary it was not the point of the course. Still, every class had presentations with tons of names, dates, terms, and concepts. So I had to figure out how to overwrite the conditioning that all of my students entered the class with: see name, write name; see date, write date. The content was there, and they could refer to it, and we would talk about it, but it was never the point. If they got preoccupied with the content trees, the historiographical forest would remain unexplored.

And, so long as we’re considering the relationship between event, record, memory, and interpretation, I tell students at the first lecture, we might as well experiment with these things ourselves.

I introduce the role of the class scribe. The rules are simple:

- All slides and presentations will be available to the class after the lecture, for reference. (Read: you don’t have to be afraid of “losing” this information)

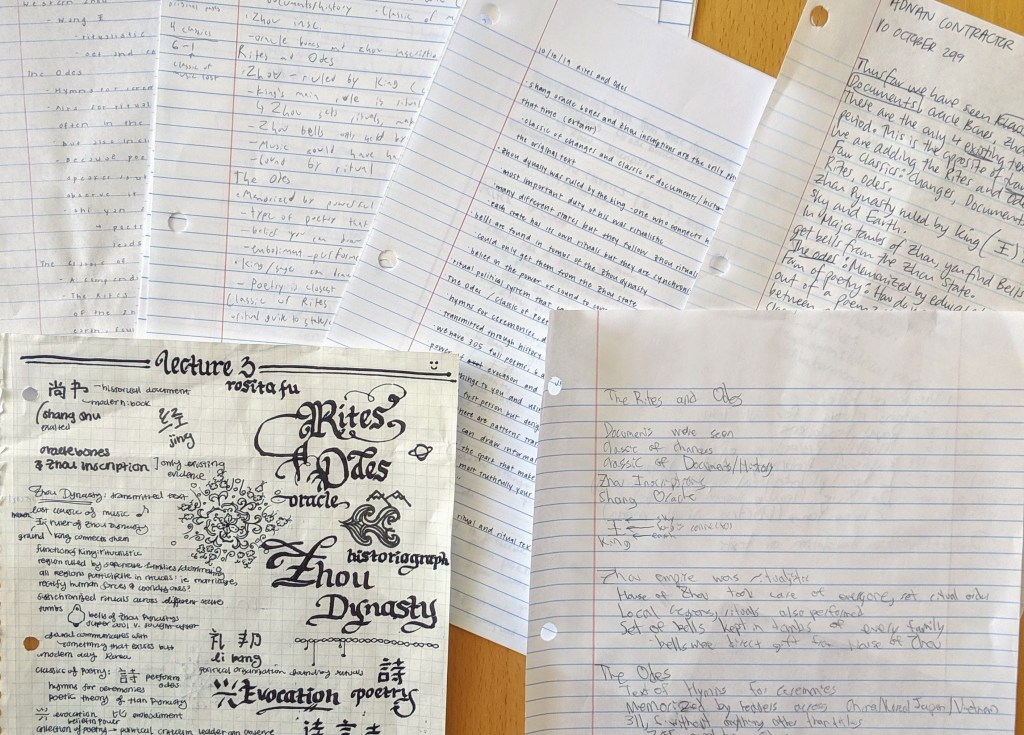

- Each student can use one piece of paper and one writing utensil to make whatever notes they want on the lecture and discussion.

- At the end of class, all of the notes are collected and given to a student (we rotate throughout the term; everyone takes a turn).

- That student will compile one “authoritative” version of the notes for the class, and distribute it.

- If you write your name on your notes, and if the class scribe from that day remembers to bring the notes back to the instructor, you can collect them at the end of the quarter.

That’s it. There are no rules about what format the compiled notes should take (although they distribute it via email). When they joke about possibly not putting any effort into it, I encourage them. Go ahead and destroy the content. What would happen then? Why do the notes matter? When they apologize for delay (sometimes the notes don’t arrive in our inboxes for weeks after a lecture), I tell them I don’t care. I tell them I wouldn’t care if they never arrived.

They think I’m loopy. They think they’re being tested. Early in the quarter, I catch students furtively taking photos of their precious notes with their phones before they turn them in, lost forever, doomed to gather dust in some freshman dorm until they’re discovered and discarded, forgotten and unloved. Those poor, precious notes.

Some of the summaries are truly cringe-worthy. Sometimes the exact opposite of what I said is the thing that the class scribe understood, and not even a whole pile of notes dissuades them from their error. Sometimes students put little jokes in the summaries, or record “non-content.” Sometimes students doodle on the page, leaving little messages or pictures for the scribe. Sometimes students do a beautiful job of summarizing the class. And I tell them every week that it doesn’t even matter.

By the last week of class, students’ sheets get more and more sparse. The learning becomes about whatever you’re thinking of, whatever you’re working on, whatever seemed important enough to remember. The content becomes the vehicle. What we’re doing is… something else. But it’s right here, it’s right now, it’s between us, and it’s in the work. It’s in the conversations they’re having with one another while they read together. It’s in the projects that they create. It’s in our discussions during office hours. It’s a process, and not a product.

By the end of the term, my desk has a little pile of notes. Usually about half of the total, probably. Never once has a student come by to collect their notes.

Bonus point: with this method, students don’t even bring their computers to class.

Anyway. It’s not an arrangement that would work for every class and for every instructor, but by devaluing the note-as-knowledge-unit, by insisting a turn away from the hear-it-prep-it-test-it construct, I am able to signal that the classroom is not a content delivery vestibule, and I am not there dispensing Things that Will Be on The Test.

Also, skimming over their notes at the end of the quarter is a great form of feedback. And sometimes it makes me giggle.